By James Fitzpatrick & Jack Banister

AFL powerhouse Collingwood has been in the spotlight since the Do Better report, an independent inquiry into structural racism at the club, was leaked to the Herald Sun in February.

The report calls upon the football club to be actively “anti-racist”. But what does that mean?

We checked in with Banksia Strategic Partners’ Special Advisor and Collingwood supporter, Abul Rizvi, to discuss “anti-racism”.

Do Better, the title of a report into structural racism at Collingwood, arguably Australia’s biggest sporting club, is also a call-to-action for businesses everywhere.

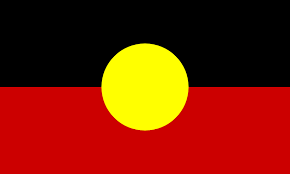

Leading First Nations footballer Eddie Betts told The Age as much this month, saying that all clubs should examine the report and its recommendations to help them create safer spaces for First Nations people, and for people from other multicultural backgrounds.

The report was commissioned after months of public criticisms and complaints by former Collingwood footballer Heritier Lumumba. Its authors, Professor Larissa Behrendt and Professor Lindon Coombes, made 18 recommendations in 8 different categories.

The first of those recommendations calls upon Collingwood to “undertake a process to integrate concepts of anti-racism and inclusion as qualities inherent in the Club’s values”.

But what does that look like in practice?

Abul Rizvi, Banksia’s Special Adviser, has significant experience working with policy pertaining to race, having spent 15 years as the Deputy Secretary of the Department of Immigration.

He was awarded the Public Service Medal and the Centenary Medal for services to the development and implementation of immigration policy, including the reshaping of Australia’s intake to focus on skilled migration.

A Collingwood supporter since 1968, Abul was “disappointed” by the report, and the way it was initially handled by Club President Eddie McGuire, who resigned after calling the report’s release “a historic and proud day for the Collingwood Football Club”.

Abul has three main pointers for his beloved club, and for any other organisations aiming to “Do Better” in this space.

Find people who live anti-racism everyday

A critical part of an authentic culture of anti-racism, Abul says, is to quickly identify the people within your organisation who already live it as a core value.

“You have to identify the people already in your organisation who have a belief in anti-racism to begin with,” he says.

“If it’s not championed by people who staunchly believe in it, you’re really not going to get far. If it’s just the boss doing it because they think it’s needed, or because it’s what the board has asked for, it’s not going to work.”

Empowering those people to drive change can ensure that reform isn’t just a box-ticking exercise.

The public, Abul says, can quickly spot when an organisation is pursuing an anti-racism strategy as an end point in and of itself.

“They (the public) will recognise a politician or leader who is talking about anti-racism or multi-culturalism in a fake way. They’ll see through that very quickly,” he says.

The “Do Better” report emphasises the need for several policy changes, especially around avenues of complaint when incidents of racism occur.

Ensuring that the development of those procedures is led by people with a genuine belief in anti-racism will mean those policies are thorough, and that the rationale for having them in place is firmly understood throughout the club or organisation.

Don’t lecture. Listen.

Once you’ve identified the people within your organisation who can drive change, Abul says that the next step is “to avoid lecturing and to do more listening”.

It should go without saying that listening to people of colour is of paramount importance.

In Collingwood’s case, adequately listening to and addressing Heritier Lumumba’s experiences of racism at the club when he initially raised them in 2017 would have allowed them to learn and improve as an organisation much sooner.

In addition, Abul says that it’s important to listen to people who may hold a racist attitude, with a focus on education.

“The more openly people can talk without the fear of being denigrated, you can then start to make progress because you can come to more common understandings of the issue of racism and its origins. That’s more powerful than a culture where everyone snaps to attention because the boss says they must.”

Aside from helping to create a culture of ‘anti-racism’, listening more is an essential crisis communications tool.

Eddie McGuire opened his press conference by stating the report’s release was “a historic and proud day for the Collingwood Football Club”, and subsequently spent six minutes discussing his club’s good work and the broader context of the report, rather than apologising to the people directly impacted by racism at the club.

In doing so, he quickly created the impression that he was avoiding responsibility, rather than listening and taking ownership of past mistakes.

When he did apologise, after more than six and a half minutes, he did not refer to any victims of racism, or demonstrate real empathy and understanding. It is also significant that it took several years for McGuire and the club to address the allegations made by Heritier Lumumba.

The public outcry that followed, and ultimately McGuire’s resignation, is evidence that his approach was ineffective on every front. He would’ve been much better served if he had adequately listened – and acted – much, much earlier.

Make diversity a point of celebration

As Deputy Secretary of the Department of Immigration, Abul played a role in the development of the Howard Government’s first anti-racism strategy.

A key learning from that experience, he says, is to make diversity and difference a strength, and something that is actively celebrated.

“They (The Howard Government) pursued an anti-racism strategy that introduced the idea of Harmony Day,” he says.

At a similar time, Howard famously referred to “the black armband view of history”, an idea initially coined by conservative historian Geoffrey Blainey.

Blainey was describing a view of history which, he believed, denigrated much of Australian history before multiculturalism as a disgrace.

And while Abul stresses that he doesn’t agree with that “black armband” view, and that it’s vital to reflect upon and learn from our history, he says that he agreed with the idea of Harmony Day.

“I did agree that making it a celebration of our diversity and understanding the extent to which our community, or indeed our club, is diverse is an important element of it,” he says.

The Do Better report is available in full here.

If you’re interested in strategic communications or have questions about anything discussed here, don’t hesitate to get in touch to see how Banksia Strategic Partners can assist.