By Abul Rizvi

The 2020 Budget will include the biggest reversal in any Australian government’s forecast of population growth – ever.

Last year, in the 2019 Budget, the Government forecast population growth at an average of around 450,000 per annum over four years – a sustained level of population growth that Australia has never before experienced.

This represented a population growth rate of around 1.75 percent per annum. It underpinned forecast real economic growth rising to 3 percent per annum, the Prime Minister’s promise to create 250,000 jobs per annum over five years and growing budget surpluses for the next ten years, inclusive of large income tax cuts.

Population growth driven by immigration has been a key to Australia’s continuous economic growth between the 1991 recession and the 2020 COVID recession.

But that is now history.

For the period 2019-2023, the Treasurer will announce a population forecast in the 2020 Budget that will likely be around 1 million less than was forecast in the 2019 Budget. In 2020 and 2021, the population growth rate may fall to around 0.5 percent per annum – our lowest rate of population growth since 1916.

For the period 2019-2023, the Treasurer will announce a population forecast in the 2020 Budget that will likely be around 1 million less than was forecast in the 2019 Budget. In 2020 and 2021, the population growth rate may fall to around 0.5 percent per annum – our lowest rate of population growth since 1916.

Net overseas migration in 2020 and 2021 may in fact be negative – not only for the first time since 1946 but the first two consecutive years of negative migration since the Great Depression.

Due to its political sensitivities, the change in population is both one of the most important yet most hidden in the budget papers. The Government rarely provides details on how it arrived at its population forecasts hence it is important to have some benchmarks against which to judge how robust the Government’s forecasts may be.

I have undertaken my own calculations of the likely population growth forecast in the 2020 Budget. For this purpose, I have assumed:

- Overseas arrivals cap increases from 25,000 per month to 40,000 from January 2021 with a particular focus on overseas students and Australian citizens and permanent residents.

- Fully open travel bubble between Australia and NZ to start from February 2021.

- Travel between Australia and most other nations, particularly key source countries for students and migrants, does not open up without some form of quarantine until start of 2022.

- Migration and Humanitarian Programs are smaller and focussed on people already in Australia.

- Visa policy settings remain largely unchanged to those in place prior to COVID-19.

- Economy remains weak over the forecast period. Unemployment is above 6% as in 2014-15 when net migration fell to 184,000 despite a much larger and offshore focussed migration program.

- Suspension of 4 year waiting period for access to social security expires on 31 December 2020.

- Relations with China, our main source of students, visitors, and business migrants, remains poor.

For 2020 and 2021, I have developed monthly forecasts of arrivals and departures for each visa/citizenship grouping used by the ABS based on experience of recent months with the current overseas arrivals cap.

I have then used a revised propensity for arrivals and departures to be counted in net migration for each month and for each visa/citizenship noting restricted movements will significantly increase the standard propensities.

For 2022 and 2023, I have assumed a gradual return to normality drawing on outcomes for 2019 (i.e. latest net overseas migration data) and 2014-15 (last year in which unemployment was above 6%).

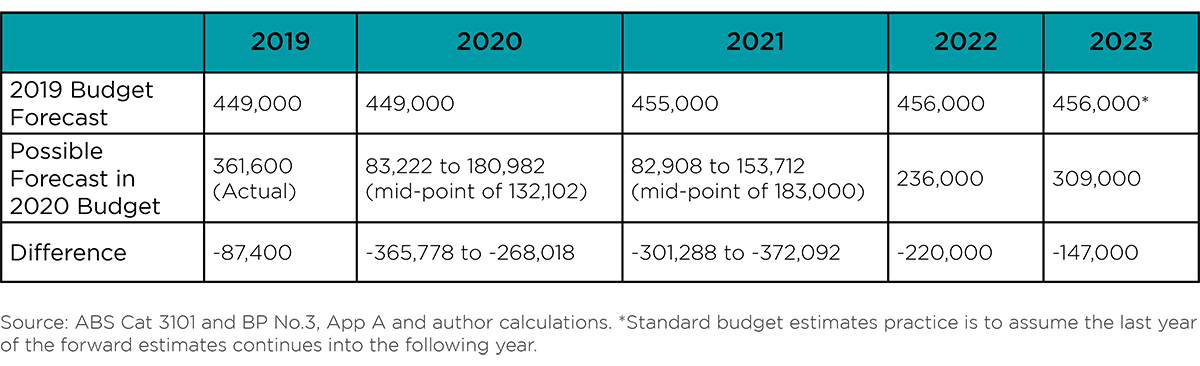

The key conclusions from these calculations are in the table below:

Population Growth Forecast

I conclude that population growth over 2019-2023 will be between 1.02 million to 1.19 million less than forecast in the 2019 Budget – partly due to COVID-19 but also due to weak economy before COVID-19 and changes to policy settings.

I conclude that population growth over 2019-2023 will be between 1.02 million to 1.19 million less than forecast in the 2019 Budget – partly due to COVID-19 but also due to weak economy before COVID-19 and changes to policy settings.

Slower population growth will accelerate population ageing. Population ageing will, all other things equal, put downward pressure on economic growth, per capita economic growth and per capita tax revenue while increasing spending pressure on health, aged-care and the age pension.

Universities, the property and construction industry, business advocates and most state governments will be urging the Federal Government to lift net overseas migration.

But the lessons of the 1991 recession show that is more difficult than just inserting some unrealistic assumptions into the Budget Papers. After the 1991 recession, it took almost a decade for net overseas migration to return to the levels of the late 1980s.

During the 1990s and the 2000s, Australia was in its demographic dividend phase where the ratio of working age to total population was rising. Since 2009, Australia has been in its demographic burden phase where this ratio has been declining.

This ratio will keep declining in the 2020s and 2030s. There is little that can be done about that.

No developed nation has achieved strong economic growth once deep into its demographic burden phase. Australia will be no different.

The above population forecasts will be sensitive to changes in immigration policy, relative economic conditions and the nature of travel restrictions.

I am pleased to have joined Banksia Strategic Partners and can assist organisations wanting to better understand how their strategic objectives may be impacted as population forecasts change under different scenarios.

If you’re interested in how your organisation might benefit from expert government or population advice or just keen to talk through some of the topics set out above, don’t hesitate to get in touch.

By Abul Rizvi

Special Adviser

Abul specialises in work on all aspects of immigration policy, including international students, temporary migration, tourists and working holiday-makers, and its implications for Australia’s population and economic direction at the national and sub-national level. Read Abul’s full bio here.